How To Cook On A Backpacking Stove

Tis an ill cook that cannot lick his own fingers. — William Shakespeare

A near tragedy: the first week out on the expedition someone lost the bottle opener, and for the rest of the trip we had to subsist on food and water. — W.C. Fields

Finally! We’re! Getting! Some! Where! Here’s the basic level of stuff you need: a stove, a pot support, a pot, and a wind screen. I also add a metal reflector to go under the stove, and a lid for the pot. Confession time: my pot isn’t really a pot and doesn’t come with a lid.

Pots

My usual pot is a 16-ounce aluminum measuring cup, once available from an outfit called “Gooseberry Patch”. It was priced at $5.95. As far as I’m concerned these are just about ideal. The cups I have are fat, short, stable cylinders with a handle on one side, weigh 1.9 ounces (54 g), and are pretty darn small, cheap, durable, and also are so easy to operate that I can even use my spare hand to scratch with and not get into serious trouble.

This arrangement has only two problems as I see it: (1) there is no lid to my pot, and (2) the handle sticks out, sorta, and doesn’t fold. For a lid, I use a piece of aluminum foil, and just swear at the handle every now and then. Mostly, we get along just fine. So far the pot has never sworn back at me. It’s too good for that. I am so ashamed of myself.

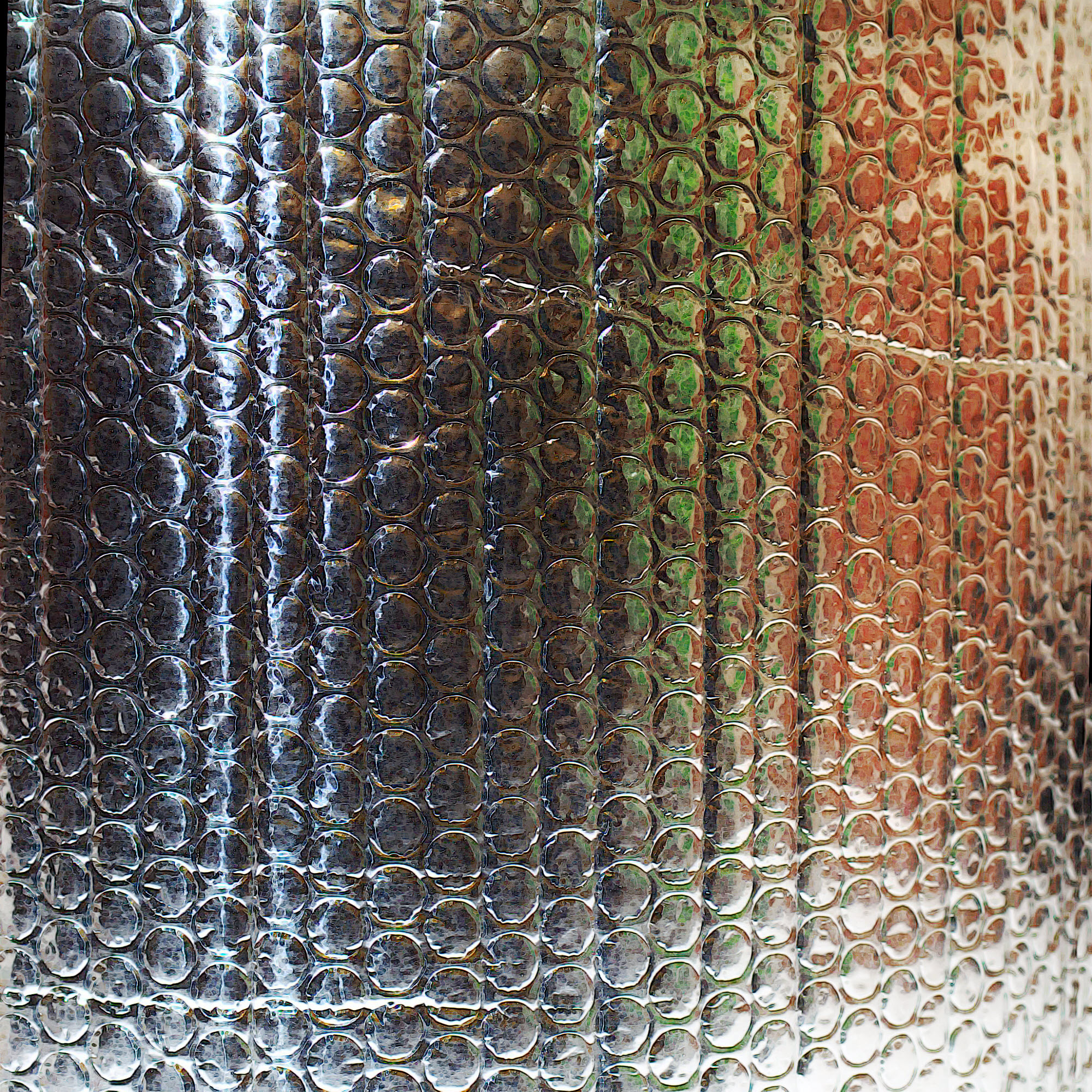

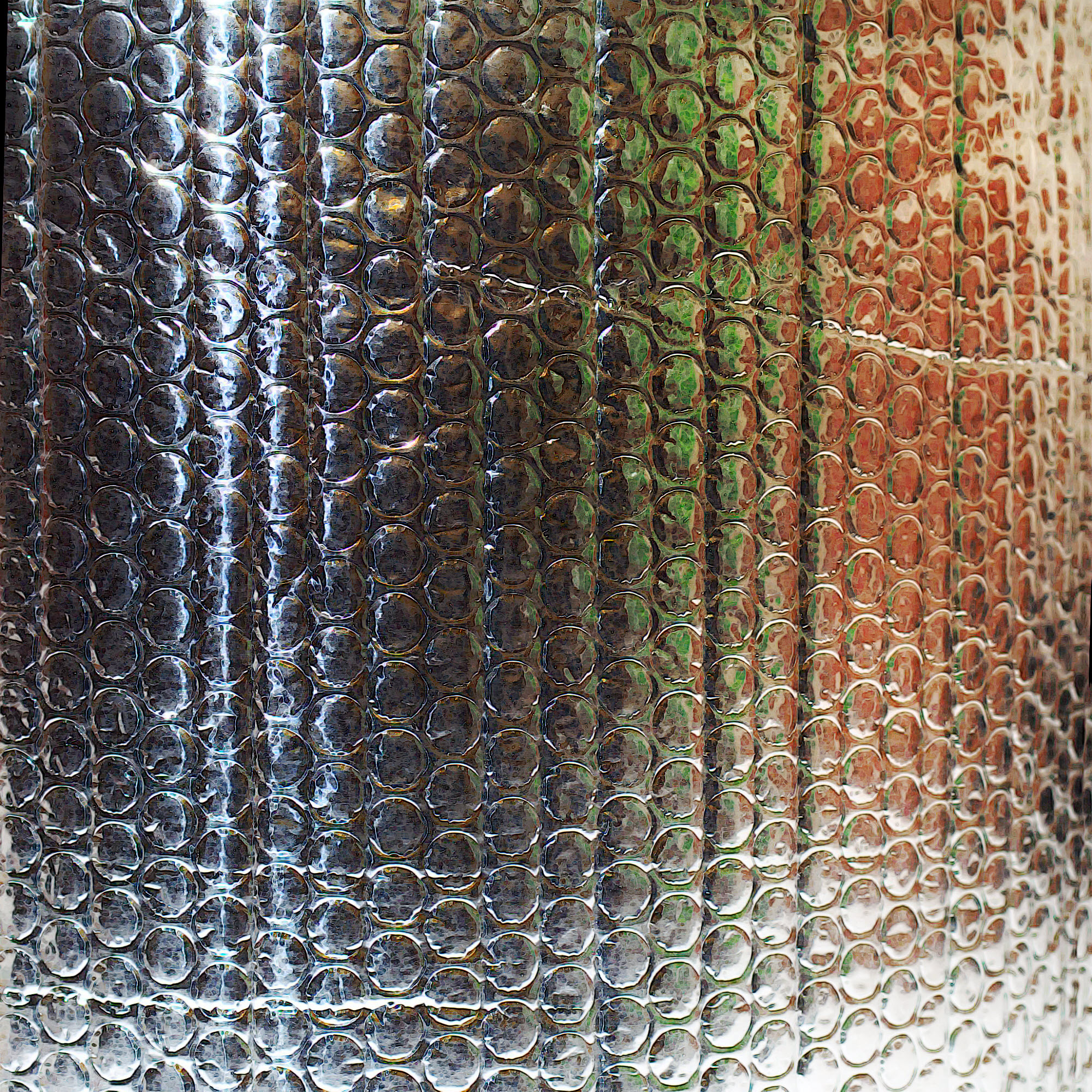

The next non-essential item that’s essential for me is a cozy of some kind. I carry my cook kit inside this, and use it to hold cooked food (inside a plastic bag) before eating it. The cozy is made of a “foil-bubble-foil” material (aluminized bubble-wrap). The stuff I have goes under the “Reflectix” brand and is available at building supply stores. You can cut it with a scissors. With heavy aluminum foil on each side and a middle layer of bubble wrap, it does a great job, and it’s stiff enough to make a nice container to carry your cook kit in. With a scissors and a little duct tape you can make any size and shape you want.

My wind screen is made from two or three layers of regular household aluminum foil. I pull off enough to form into a cylinder around my pot while it’s on the stove. (Fold over the two free ends and staple them together and you have a hollow cylinder.) The width of the aluminum foil is the vertical height of the wind screen and it’s just about right for my low-profile setup. If the inner sides of the screen stay away from the flame, it works OK. If the flame touches the foil, it gets brittle and crumbles. Therefore I makes ’em big, using plenty-o-foil. Weighs less than an ounce (28g).

I keep the wind screen folded up and either wrapped around the outside of the cooking pot (when using my 16-ounce/0.5L cup) or tucked inside if using a larger pot. That’s one nice thing about the foil: you can fold it or roll it up. With care one foil wind screen can last at least two weeks, even if used twice a day. I’ve done it.

The wind screen forms an open cylinder. One end sits on the ground and I pucker the other end so it’s almost closed, resembling a stuff sack with its drawstring pulled tight. This leaves a little hole at the top for the stove exhaust to get out, but protects the stove and pot from cold air and wind.

I take care to lift the bottom edge of the wind screen about a half inch (13mm) from the ground so the stove can get enough oxygen, and if the weather is a little too breezy, I put a small stone or two on top of the wind screen to keep it in place.

These days there are lots of options for lightweight cook sets. You really don’t need much of anything other than a metal container to heat water in. MSR, Olicamp, Evernew, Snow Peak and others make an amazing collection of gem-like titanium pots. Expect to pay $25 to $80 or more, depending on your needs. Or go cheep-cheep, and cheap out.

Wal-Mart, our beloved all-American, impersonal mega-institution, used to sell a generous-sized aluminum pot-like thingy (my best guess is 40 ounces or 1.2 L). They called it a “Grease Pot”, and I guess it’s normally bought by people who cook a lot of fatty meat, day after day, and can’t eat all the grease at once, but just can’t bear to throw the stuff away either.

You could buy one (the pot, not the grease), throw out the included strainer and the plastic knob on top, and you had a sort of pot. The last price I saw was $5.47, down from the stratospheric $6.97 I paid three years earlier. But not every good deal lasts forever. This item seems to have disappeared from the product lineup (they’re going upscale now), so check around and see if there’s still something similar, somewhere.

Use your gloves as potholders. Don’t actually cook food either. Just heat water. This keeps things clean (keeps any pot clean), and avoids dealing with a super-thin pot that easily carbonizes its contents.

If this option is too easy for you, then sniff around a low-end store somewhere, or a GoodWill, and look for cheap aluminum cookware. A company called “Mirro” is the champion. You might not want to buy a full set to show off in your kitchen but it’s just right for the trail. Cheap, light, small and simple. You may even find something with a lid. Take a look at the smallest coffee pots — after all, you’re just heating water, right?

Here’s how I carry my stove and cook set: Put the stove, under-stove reflector, pot support, and matches or lighter inside the pot. I carry a box of strike-on-box matches (usually two boxes worth of matches in one box), and protect them with a sandwich-size ziplock bag.

If the pot is big enough, stuff in the wind screen, which should go in first, curled around the inside wall of the pot. You can carefully fold and flatten this screen, into a thin band. When you’re done you’ll have a sort of flat strip about two or three inches wide (50 - 75mm) and as long as your roll of aluminum foil was wide. When using my 16-ounce measuring cup, I wrap it around the outside, since the cup is way too small to hold the wind screen and the stove and so on.

When done with all this folding and stuffing, put the whole thing inside your pot cozy, and then inside a gallon-size ziplock bag. The bag keeps everything together, keeps dust, dirt, bugs and twigs out, and protects your pack from absorbing food odors. It also keeps food odors in, so you aren’t trailing a scent stream behind your blind side as you walk along.

Utensils

I munch a lot of mooshy stuff, cooked in a ziplock bag, and used to eat out of the bag using a spoon. One day the spoon broke. Oh, noes!

After sitting down for a while to decide if swearing and waving my arms around would really help, I decided that it wouldn’t, so I made double sure that the bag of warm, cooked potatoes was tightly sealed, rolled over that end a turn or two to be extra double sure sure, held it tightly, and tore one corner off the bottom of the bag with my teeth. Then I squeezed the potatoes out like squirting toothpaste from a tube, into my mouth. Guess what? Works great, and now I never carry a spoon.

Now I don’t have to keep track of a spoon, replace one that breaks, or worry about whether licking it off after each meal is really the same as washing it.

Fueling

Let’s stick with alcohol stoves here. We’ll mention wood stoves later on.

To fuel an alcohol stove, first you have to carry fuel. I use a Platypus brand half-liter bottle. My old-style “Li’l Nipper” bottles weigh 0.7 ounces (20 g) empty. Newer bottles of the same capacity are probably close. These are small enough to be handy, but hold enough for several days, and if you squeeze out the excess air you don’t find them expanding to the danger point if you gain a lot of altitude. With hard-sided bottles you can’t remove the air unless you fill them to the top, or carry them nice and flat inside a pack pocket. And with the Platypus bottles, you can easily bring two for longer trips, or to split your fuel into two packages so you won’t be totally out of luck if something happens to one bottle.

Back to our story.

The cap on all Platypus bottles holds 0.25 ounces (7 ml) of fuel, so it makes a good measure. Usually, for 16 ounces of tea, using treated water (so it doesn’t have to be boiled), about 1.25 to 1.3 caps full will do the trick, bringing 12 ounces or so of water up to just short of boiling temperature. After the tea has steeped I can add cold water to get it down to drinking temperature, and have at it. Instant coffee would be easier — you wouldn’t need to get the water so hot, so you could use less fuel.

To fill the stove, pour fuel from the bottle into the cap, being careful not to spill, then with equal care pour it into the stove. Put the cap back onto the fuel bottle and squeeze the air out before tightening down the cap. This prevents pressure buildup in the bottle (and possible leakage) when you gain a lot of altitude.

If you set the fuel bottle down while you’re filling the stove, you stand an excellent chance of having it fall over and spilling all your fuel, so watch out.

I tried a push-pull type cap for the fuel bottle, but mysteriously kept losing large amounts of fuel, even while being careful to carry the bottle absolutely upright in the pack. The push-pull cap is one that telescopes open when you pull on it, and pops closed when you push on it — no screwing off and on again. It was just loose enough to let the alcohol vaporize and leak out of the bottle. This was not at all funny when I got halfway through a trip and ran out of fuel, so expect the same results if you go this route.

Priming And Lighting

There are two kinds of people: bigots, and good, reasonable folk who agree with me.

Likewise, you can say that there are two kinds of stove: those that need priming and those that don’t. I don’t like to prime a stove. The alcohol stoves that don’t need it are non-pressurized. They range from a simple cup to fancy and esoteric constructs of baffles, conduits, air holes, and multiple walls. Non-pressurized stoves have the fuel open to the air, so you can stick a match in there and light it. We’ll see more on these topics in the section on making stoves.

Conversely, pressurized stoves have to be sealed up while they’re burning, so you can’t just light them right off. You have to fill the stove, seal it up tight, prime it by dumping some fuel somewhere, light that, let it burn, AND THEN light the stove.

You get to choose your own preferences, but for me, I like to keep it really simple, and use a non-pressurized, non-priming stove.

These stoves are really easy to use. Just add fuel and light. If the weather is cold (like under 40 degrees F/22 C), you may have to stick the match almost into the fuel to get it going. Using a cigarette lighter with cold fuel is a lot harder than using a match, so that’s why I prefer matches, though I always carry a lighter as a backup. Using a fiberglass wick reduces the cold weather problems to almost zero.

To light a cold stove using a cigarette lighter, you have to flick the lighter on, then turn it so the flame is pointing down, and then sort of stick the flame into the fuel until it catches. Well, guess what? The flame doesn’t like to burn downhill. It always curves back up again and gnaws on my fingers. Ow! I can’t take much of that, so I use matches.

Snuffing And Storing

Some alcohol stoves allow differing degrees of simmering. If you get into that end of things, you’ll eventually end up with some excess fuel left in the stove. The Swedish Trangia commercial stove has both a simmering option and a screw-on top that allows you to keep unused fuel right in the stove.

Home-made stoves have no screw tops to keep unused fuel inside them, so they need to be emptied of excess fuel. This can be messy. You’re guaranteed to get most of the fuel spilled on your hands, over the sides of your fuel bottle, or on the ground unless you go to the trouble of carrying a funnel. More things to keep track of, and more fuss, and even a funnel won’t really solve the whole problem.

The Trangia stove is pretty good in this regard, with its fancy screw-on lid with O-ring and all, but the stove alone weighs three ounces (85g), so it’s outside our arbitrary limit for ultralight stoves, but it might suit you nevertheless. REI (Recreational Equipment, Inc.) sold me a complete lightweight Trangia outfit with stove, pot support, pot and lid, and pot lifter for about $30. Total weight, just under 12 ounces (340g). This is the alcohol-burning outfit I started with, before eventually deciding to make my own.

Staying really simple, you can just heat water for tea, coffee, cocoa or whatever else excites you as a hot drink, and heat water for all your cooking. If you do that, and don’t simmer or cook in the pot, you can keep things clean. Learn to measure out the right amount of fuel, dump it into the stove, light it, put on the wind screen, and come back when the fuel has burned out. Forget about fussing with simmer rings and draining the stove. And about washing pots.

But these ideas are only a guide. You yourself have to decide what’s right for you.

Exercises

- If you haven’t cooked outdoors before, learn how before your first backpacking trip. Try cooking in a local park (yes,one that allows it). Work out your technique before you commit to a real backpacking trip.

- Start a blog. Seventy-five thousand people a day do this, so why not you? I mean, c’mon! You’ll eventually find something to write about.

- Remember, today is the first day of the rest of your life. This is especially true if you’re in the witness protection program. Don’t try to contact me. Too dangerous for both of us. Go back and delete that blog thing too. Right now.

- Make your first trip to Wal-Mart. It’s a little like going to another planet. Keep your guard up, or let it down, as appropriate.